This past July, my daughter and I flew across the country, from New Hampshire to California, and set about building a new life. My husband met us at the airport. We hadn’t seen him in a few weeks; he’d driven his car across with our dog and cat.

Originally, we had thought we’d caravan — one car following the other, a chance for the three of us to see the country. But then we’d opened the map: mile upon mile of land where our daughter did not have basic human rights. I shipped my car and booked a flight.

“Do you really have to do that?” my mother asked, when I called to tell her. “How in the world would anyone ever even know she’s trans?”

It was the same question my daughter had asked me a few weeks earlier, when I’d sat her down to talk to her about the legislation sweeping our state and rewriting our lives. I don’t like to talk about politics with my daughter; she’s only 12, and she has to go to school, and interact with all kinds of people. It’s hard enough for adults to navigate our polarized country. But she — her actual, physical self — has been identified as a political issue. There’s only so much I can shield her from.

Knopf

Five years ago, when my daughter was just shy of her seventh birthday, our small New Hampshire town erupted in school board fights about her. Neighbors and strangers came out to stand at the podium and claim that she — a child who still sat in a booster seat — was a threat to our community. We kept our curtains closed. At school, classmates constantly told our daughter that she wasn’t a girl and wasn’t allowed to change her name.

They misgendered and deadnamed her and, because the superintendent had made a rule that the word ‘transgender’ could not be used in the classroom setting, the teachers were powerless to educate the students to stop the bullying. Eventually, the ACLU and GLAAD had to get involved and we had to move. We went to a nearby city, because it was the early days of the pandemic and we couldn’t find new jobs, and more importantly because the New Hampshire governor — the very same one in office today — had just signed a nondiscrimination bill into law, meaning (we believed) that at least in our state, our daughter had equal rights.

That move took place in the summer of 2020. At the time, despite what we had been through in our town, we were totally unfamiliar with the state-level anti-trans legislation that was about to spread like wildfire across our country. A sports ban had recently passed in Idaho, but it hadn’t gone into effect yet, and its prospect seemed so ludicrous—an entire state banning certain children from kindergarten onward from joining sports? I’d had no idea that the terrorization we’d endured in the home my grandparents had lived in, the town my father had been raised in, the county my family had been in for hundreds of years, was about to unfold in state legislatures across the country.

That winter of 2021 — the first in our new home — I found myself embroiled in something that I’d been privileged enough to never really notice or understand before: the state’s annual legislative session, and with it the horrendous and impossible act of explaining in three minutes or less why my child’s life depends on the votes of absolute strangers.

I testified against two New Hampshire bills that winter, one that would ban my daughter from sports, and the other that would ban her medical care and criminalize her doctors and parents in the process—an act that, in its worst iteration, could end up with our daughter being removed from our home and forced to live as a boy. My hair turned gray and I suffered migraines; meanwhile, my husband woke at all hours, panicked that our new home had so many doors. When strangers came to find her, how could he possibly keep them out?

It was a crazy thought, but it also seemed rooted in reality; just one year before, a man we didn’t know had stood at a podium in our former town and announced to the school board that he wanted to find our child, to scoop her up and bring her to a loving home. How far would people like him go?

That year, the anti-trans bills that I’d testified against were stopped, meaning that at least for the time being, our daughter did not lose her rights.

The following year, in the winter of 2022, my daughter heard on NPR that the governor of Texas had issued a directive for families like ours to be investigated for child abuse. She was nine years old, all dressed for school, buckled in and waiting for me to finish scraping the ice off the car. She wasn’t naive to discrimination, but she also wasn’t aware of how widespread and dire the situation had become. That winter, I had to really explain it to her — the bathroom bans, the sports bans, the medical bans that were on the rise across the country.

Kate Criscone

The anti-trans bills were in New Hampshire again, too, and I had to explain to my daughter why I was too tired to cook dinner, too tired to play a game.

Her dad and I fought against four anti-trans bills in the New Hampshire legislature that year. As with the previous year, one of the bills threatened our daughter’s medical care and one threatened her access to sports. Another bill aimed to remove my daughter and all trans youth from the nondiscrimination law that had passed just a few years earlier; and the final bill sought to repeal the state’s ban on conversion therapy. I would wake in the night terrified, electrical volts radiating through my body, panicked that the stress of fighting for my child would kill me — literally stop my heart — and if I died, how could my husband possibly protect her alone?

Again that session, the bills in our state were stopped. We were awash in relief, but we were also not fooled. My husband had started to envision himself as a human shield, and I saw myself holding my finger in a dike, hopelessly trying to block the flood aimed at my child. The dam had already broken in nearly half the country; banning transgender kids from sports and medical care was becoming the norm.

Our daughter was growing up, and this was the water she was swimming in; she was learning to expect that people would not accept her as a human being, and by fifth grade she had panic attacks in the school parking lot before getting out of my car. Inside the building, she retreated into a thick shell, unable to work, unable to interact. What else would be the result, when a child has become the center of a political battle and is left alone to discern whether every single person she interacts with accepts her most basic self?

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE’s free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer , from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

The legislative session of 2023 brought four more anti-trans bills to New Hampshire. The most threatening to our lives included yet another bill to criminalize our daughter’s medical care; a massive bill that would ban not only her medicine but also ban public schools from affirming or educating about LGBTQ+ youth and re-legalize conversion therapy; and, finally, another bill to block our daughter from sports by removing her from nondiscrimination protections.

My daughter had joined a school ski group by then, and I’d been amazed to see how it helped her thrive. The data tells us that sports improve nearly everything in a child’s life, from grades to social skills to mental health, but seeing it in action still felt profound. Previously, when she fell, she would get angry, slam her poles on the ground, cry, and beg to go home. Skiing with a group of peers taught her to get right back up and try again.

She and I would ski together at night, when the high school team practiced. As we rode the chairlift and watched the racers below, I’d point and tell her that I used to race like that, sometimes on that very same trail. She’d ask me if she could join the team when she was old enough. I’d tell her that of course she could, knowing that I would have to work so hard to make my words true.

That winter, I once again testified against the state’s bills. Fragments of them all still come to me in the night: a legislator announcing that she wants to hang the skeletons of trans children from the ceiling to prove that they are different. Another legislator asking a teenage girl who was missing school in order to testify for her right to continue on her soccer team—where not a single teammate even knew she was trans—to please state her weight.

Once again, the bills in our state were stopped that year, but then came the legislative session of 2024. Eighteen anti-trans bills were filed in the state of New Hampshire.

Our daughter was in middle school by then, where kids threw around anti-LGBTQ+ hate speech and wore Make America Great Again t-shirts. She could scarcely make it through a day–and often, she didn’t even go. Her dad and I weren’t sure it mattered. If the bills passed, we wouldn’t send her anyway–not to a school where she couldn’t use the girls’ bathroom, where she couldn’t join a team, where it was illegal for her teachers to talk about who she was.

And anyway, how could her dad and I even worry about school when a medical ban had passed in half the country? This time around, we were up against multiple medical bills in our state. One of them would render us and her doctors felons if we still found her care. Its passage no longer seemed impossible; six states had passed a similar bill.

It was mid-March when I got a text message from my mother. She wanted to know if I’d heard the news–the New Hampshire House had voted to ban trans girls from sports.

Over the years, I’d wondered if we would really leave the state when a sports ban came, or if we would wait for a medical ban to kick us out. But I read that text and I knew. If we meant to give our daughter a fighting chance in the world, we had to go. I got up and just started throwing our stuff in piles: keep, get rid of.

At first, as I gave away my belongings, I lied to my daughter. I told her I was doing spring cleaning, because how to explain to a child that her home state was about to memorialize her bullying into law? Eventually, I had to come clean. I started the conversation with the impending sports ban, and that’s when she asked the same question my mother had asked: How would anyone ever even know?

When my mother had asked me that, I’d lost my temper. “What if you had to drive through a state where you knew it was illegal to use the bathroom?” I’d yelled. “What if we get in a car accident and she needs medical care?”

I was kinder when my daughter asked the question.

“What?” she’d cackled. “Are they going to inspect us all at the top of the ski trail?”

I did not tell her that the law did include a right to medical inspection. I just told her the truth: the fact that she is trans is out there, because she is out. It’s in her school file, and because her dad and I have been fighting for her rights since she was six, it’s on the internet. She would be banned from joining her ski team.

On Friday, July 19, 2024, when the New Hampshire governor signed three anti-trans bills into law, my family finished unpacking in our new apartment in California. Most of the moving van had been filled with our daughter’s things; we’d paid nearly $5,000 to move her Legos, Nerf guns and stuffed animals across the country, because it seemed like a small consolation prize — You got kicked out of your home, but hey, you get to keep all these toys!

My daughter’s started middle school in California now. For the first time in her life, she’s safe to be herself. She, like her dad and I, have started to have an odd feeling that takes us a moment to name. Happiness. We want to be in the world again. We want to be alive.

Yesterday was different, though. I had that same old exhaustion, that sense that a poison coursed in me. My daughter could tell, and she wanted to know why, so I told her that I was trying to write this essay, trying to show in 2,000 words or less why trans people required rights.

“That sounds easy,” she said. “I could do it in five.”

I asked her what she’d say.

“Duh,” she said. “Trans people are human beings.”

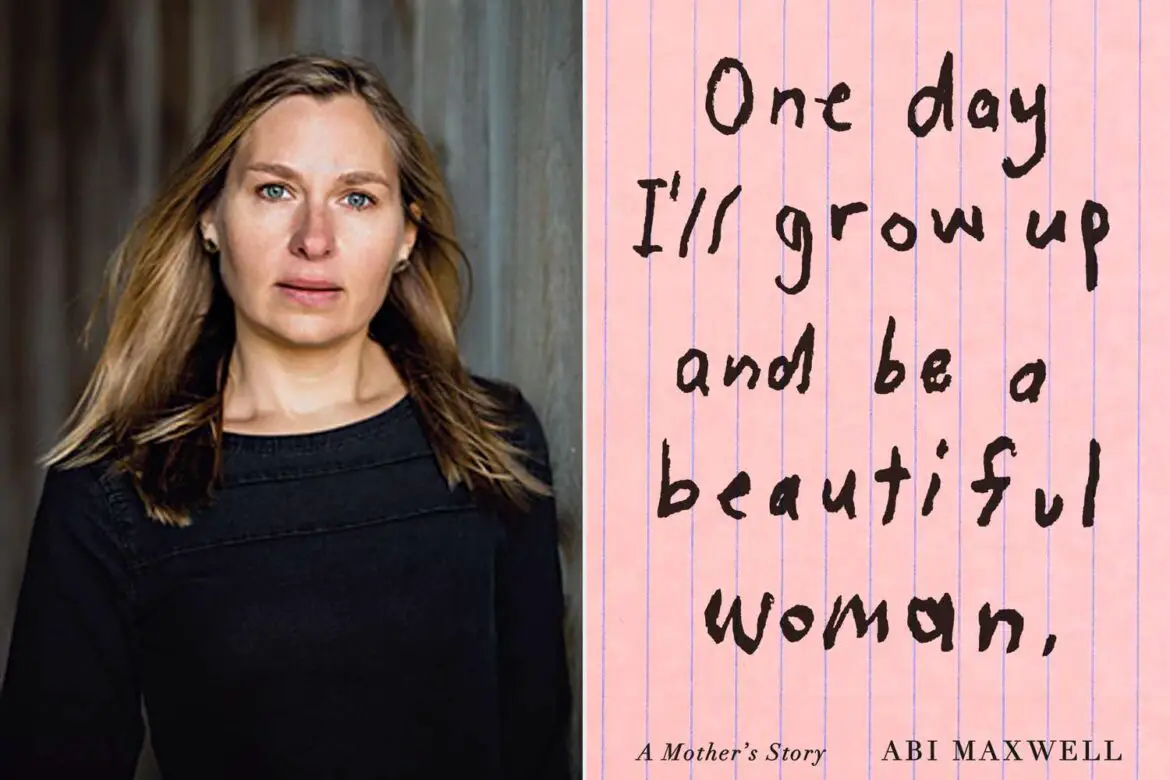

Abi Maxwell’s new book, One Day I’ll Grow Up and Be a Beautiful Woman: A Mother’s Story, is available now, wherever books are sold.