“Long time, no see!” My dad’s voice was filled with joy and warmth for my daughters who peeked into my parents’ bedroom to see if they were awake.

“We missed you O.D. and Ren,” my dad said to my two youngest daughters Odessa, 12, and Renley 8, giving them big hugs. My eldest daughter, Emerson, also got the five-star treatment when she popped in to say hello after her track meet.

My brain registered these little moments because his tone was so different from the greeting I received earlier in the day when I welcomed my parents back to New York. They were returning from a two-week trip to Vietnam, their 14th visit to our birth country since they escaped with me in 1980, when I was just a baby.

For me, it was a glance and a nod, my dad busy texting on his phone, as I hugged my mom before hauling their luggage, Styrofoam coolers and heavy cardboard boxes into the garage. “Just leave it here. I take care of it,” my dad said.

I knew I’d have time later to ask about the trip, hear about my aunts and uncles and watch dozens of videos of them with relatives, riding gondolas and kayaking in H? Long Bay. But as I overheard my dad saying hi to my kids, it clicked for me: These were not the same people who raised me.

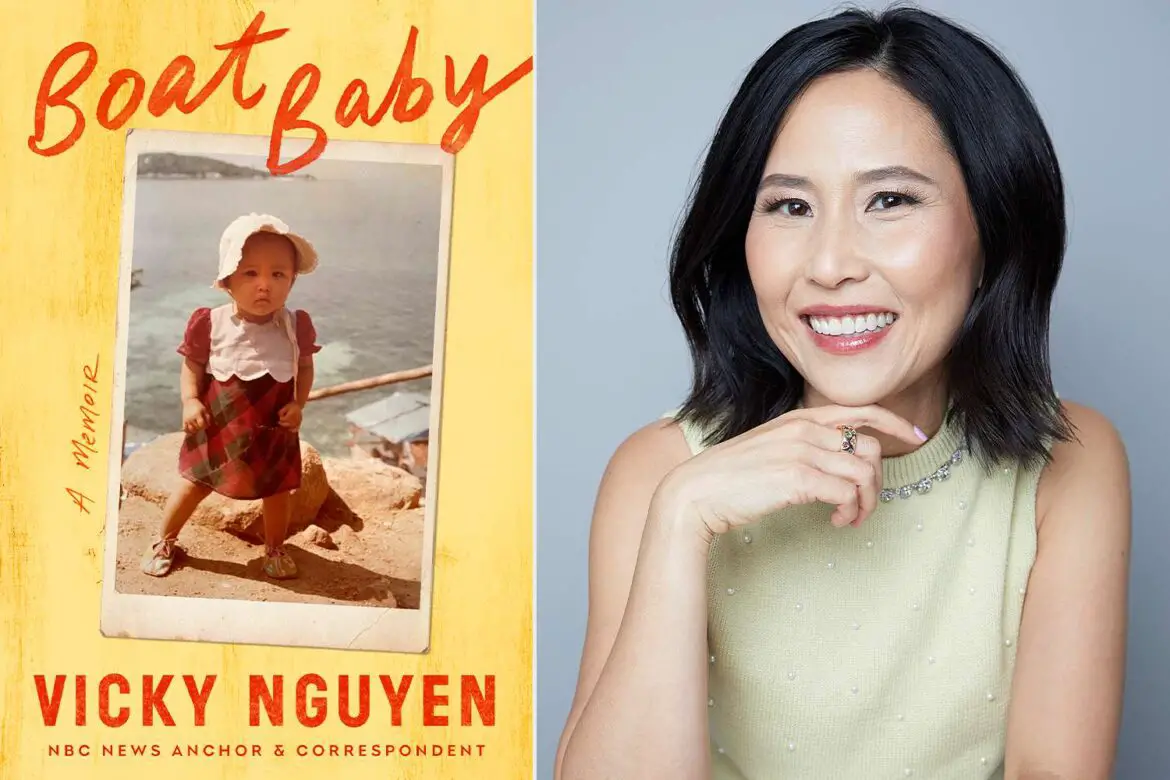

Courtesy of Vicky Nguyen

When I was growing up, we didn’t share hugs and open affection. “I love you,” a phrase I hear them say often to all three of my daughters, is one I rarely heard as a kid. While my mom and I have always been close, it wasn’t until college that we hugged and exchanged I love you’s regularly. And even now, I can’t even think of a time my dad has said those words to me — ever! It’s a funny thing about Asian families. The love my parents have for me has always been expressed through actions more than words. It took me a long time to understand that.

Growing up, I noticed my friends’ parents applauding their report cards or telling them, “I’m so proud of you,” for things I thought were expected, like getting an A in a middle school class. When my firstborn, Emerson, was a year old, I couldn’t imagine saying I was proud of her. What could a child accomplish that was worthy of such high praise? Then she grew a little, started talking, and literally took her first baby steps and I thought, “My child is AMAZING. I’m so proud of her!” The realization threw me. I was becoming one of those soft parents who thought their kids hung the moon because they could pee in the toilet instead of a diaper.

But as my children grew, I marveled at how three girls from the same parents can develop astonishingly distinctive personalities. At the same time, I began to question how I was raised and what made a good parent. My parents, who didn’t know back to school night from Back to the Future, who didn’t pay attention to the struggles I had with friend groups or bullies, who left me to figure out school and a social life on my own were nothing like the parent I was becoming.

They raised me to be Vietnamese first. Tough love, discipline, no talking back. Parents were the authoritarians. There were no outward displays of affection or “dialogue,” just rules and obedience.

My parents worked hard to provide the Nintendo and material goods I begged for but when it came to those American expressions of love, no luck. Far from the stereotypical Asian Tiger parents, they were pretty hands-off. They relied on me to bridge some of the gaps of adapting to life in America and figured I would forge my own path.

But I’m much more American in my approach to parenting my own daughters. I try to help them problem-solve, and I can relate to them so much more easily because we don’t have any language or cultural barriers. And I tell them I love them all the time. Sitting at the table, when they enter a room, when they clear their dishes. I talk to them about sex, drugs, online predators. No topic is taboo. I make them cringe plenty, but our communication is a two-way street. And what I expect of them feels different than what was expected of me.

In my new book Boat Baby, out this April, I write about the humor and humanity of those struggles. I also address the financial stress I felt of becoming the breadwinner for my family in my late 20’s, especially working in the fickle field of broadcast journalism where starting salaries are notoriously low and competition is high.

Deborah Feingold

As I got older and my relationship with my parents transitioned into an adult one, I felt pressure to provide for them, which made our bond feel transactional at times. But as we plowed through our financial lows, I learned to recognize that not everything valuable can be measured in dollars. Our family has stuck together through a lot of tough times because splitting apart was never an option, even when it seemed easier.

It’s like Kintsugi, the Japanese art of putting broken pottery pieces back together with gold. Every break is unique but when you mend it, you can actually create something stronger and more resilient. When my kids arrived and my mom and dad became grandparents, I began to see them in a beautiful new way.

Weekdays, my parents live with us in what Americans call a “multigenerational household.” In many other cultures, it’s just known as “the way it is.” Families live together, grandparents help raise the grandkids and eventually, they help take care of the grandparents. Having them with us has enabled my husband and me to thrive in two busy careers because we know that our three girls are safe, well-fed and have multiple adults who love them and care for them.

My mom and dad, who raised me the same way their Vietnamese parents raised them, are fully grandparenting as Vietnamese-American. That accounts for the hugs and kisses, the “I love you’s” when the girls leave for school or practice, and the new light in which I can give my parents more grace and appreciation for how they’ve evolved and the sacrifices they’ve always made for me.

The PEOPLE Puzzler crossword is here! How quickly can you solve it? Play now!

One of my dad’s favorite sayings is a popular one you’ll see on a lot of signs in the tourist areas of Vietnam. “Same same, but different.” Generationally we will always be different from our parents. And when cultural conflicts arise, it’s easy to put more emphasis on what divides us than what we share. But in Boat Baby, as I look back on what it took for my parents to escape Vietnam and start over in America, what they modeled for me while doing their best, I think the most important parts of what we all strive for as parents is much more “same, same” than different.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE’s free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer , from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

Simon & Schuster

Boat Baby by Vicky Nguyen comes out April 1 and is available now for preorder, wherever books are sold.